AI in Parkinson's Disease Diagnosis: Context Determines the Standard

At the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society Pan-American Congress in Houston, I participated in a debate on a straightforward question: Is artificial intelligence relevant for the diagnosis of Parkinson's disease?

Before the session began, the audience vote was almost evenly divided. Roughly half believed AI is relevant for diagnosis. Half did not. After a structured exchange and discussion, the vote remained essentially the same.

The outcome was not surprising. The disagreement reflected differences in framing more than differences in data.

When people ask whether AI is "ready" for diagnosis, they often assume a single, fixed use case. But diagnosis in Parkinson's disease is not one decision. It is a sequence of decisions unfolding over time, across settings, and under varying levels of expertise. The context of use determines what standard is appropriate.

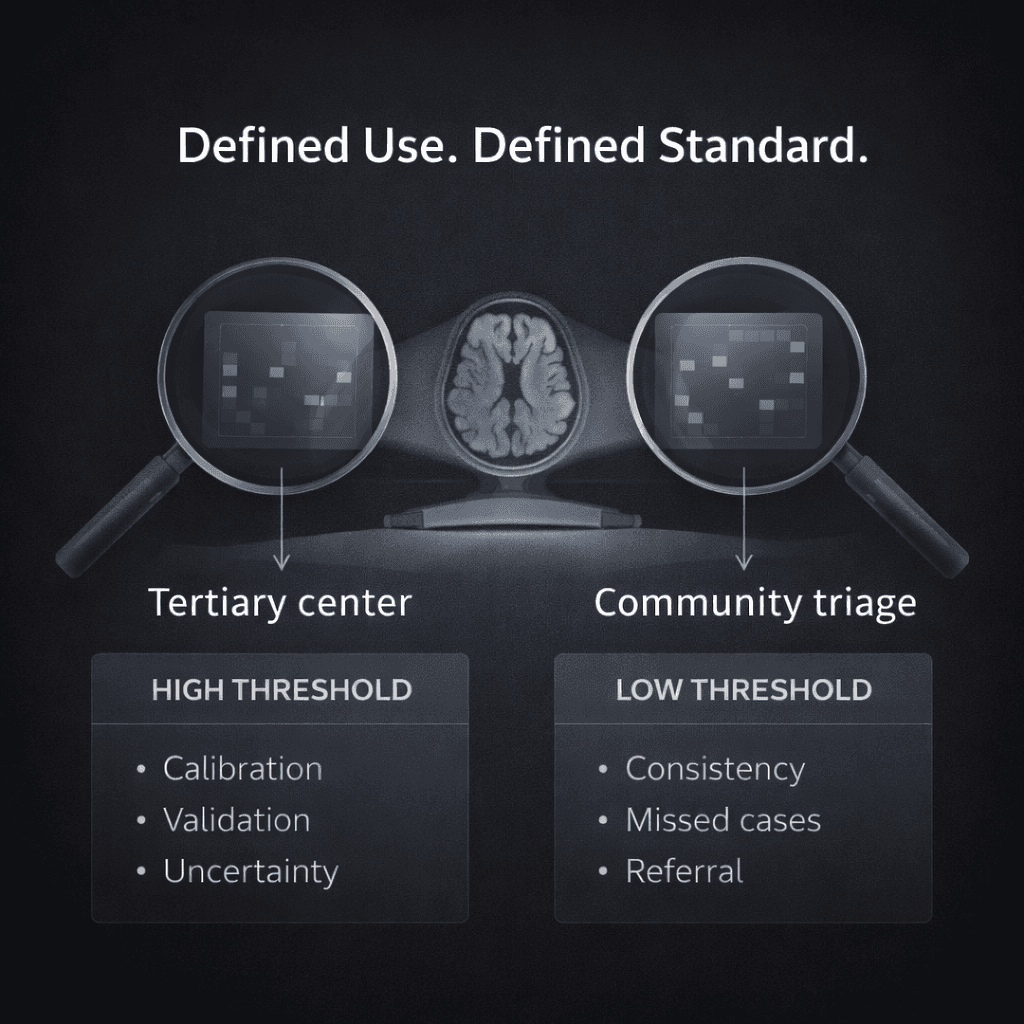

Consider two very different clinical environments.

In a tertiary referral center, an algorithm positioned as a replacement for expert diagnostic judgment would need to meet a high threshold. It would require robust external validation, careful calibration, clear reporting of uncertainty, and strong performance in edge cases where specialists themselves may disagree. In that setting, label instability and expert disagreement become central limitations.

In a community practice setting, the problem may look different. Many patients are initially evaluated by clinicians who do not specialize in movement disorders. An algorithm designed to assist with early recognition or to flag cases warranting referral operates under a different standard. In that context, improving consistency in documentation or reducing missed cases may represent meaningful clinical benefit, even if the tool does not resolve every ambiguous presentation.

The same model judged under these two contexts could be described as insufficient in one setting and useful in another.

During the debate, I framed my position around three principles: consistency, confidence, and access.

Consistency refers to reducing avoidable variability in how clinical features are interpreted and recorded. Subtle motor findings and narrative descriptions are not immune to subjective variation. Algorithms trained on structured representations of clinical data can help standardize feature extraction across evaluators and practice environments. The goal is not to eliminate clinical judgment, but to reduce variability that arises from documentation differences rather than biological differences.

Confidence refers to structured decision support in situations of uncertainty. Early Parkinson's disease often presents with subtle or overlapping features. A well-calibrated model that provides probabilistic estimates within a defined context can strengthen decision-making while preserving clinician autonomy. The role of such a tool is not to automate diagnosis, but to inform it.

Access addresses an uneven distribution of subspecialty expertise. Movement disorder specialists are concentrated in academic centers. Many patients are evaluated in settings without that depth of experience. Embedding subspecialty-informed patterns into scalable tools can extend expertise more broadly. In that context, the relevant question is whether the tool improves referral patterns or reduces delays, not whether it achieves pathological certainty.

Each of these principles depends on clarity about intended use.

Part of the hesitation in the room likely stemmed from how the term "diagnosis" was interpreted. For some, it implied definitive classification at the level of pathology. For others, it referred to structured support in recognizing and managing parkinsonian syndromes within real-world practice constraints.

These are not equivalent claims.

Clinical labels in Parkinson's disease are not perfectly stable. Experts disagree, particularly in early or atypical cases. Documentation reflects recall, narrative framing, and evolving understanding. If we treat those labels as immutable ground truth, we risk overstating certainty.

At the same time, disagreement does not negate usefulness. In clinical medicine, we make decisions under uncertainty every day. The relevant comparison is not between an algorithm and an idealized, error-free clinician. It is between an algorithm deployed within a defined context and current practice in that same context.

If a tool improves consistency in feature recognition, strengthens confidence in borderline cases, or expands access to subspecialty-informed patterns, it may provide benefit even if it does not settle every diagnostic ambiguity.

The nearly unchanged vote before and after the debate underscored how much hinges on framing. When context of use is unspecified, evaluation becomes abstract. When context of use is defined, standards become clearer and more measurable.

The question is not whether AI can "diagnose Parkinson's disease" in a global sense. The question is whether, within a clearly defined role, it improves the decisions that matter to patients.

That distinction shapes how we build models, how we define labels, and how we judge performance. It also shapes whether the field moves forward thoughtfully or becomes polarized around simplified positions.

The audience may have remained evenly divided. The conversation itself, however, reflected a more important shift: from binary judgments about readiness to a more precise discussion of purpose.